Representation of women in science drops considerably at every profession stage, from early pupil to senior investigator. Disparities in alternatives for women to contribute to analysis metrics, equivalent to distinguished speaker occasions and authorship, have been reported in many fields in the usA. and Europe.

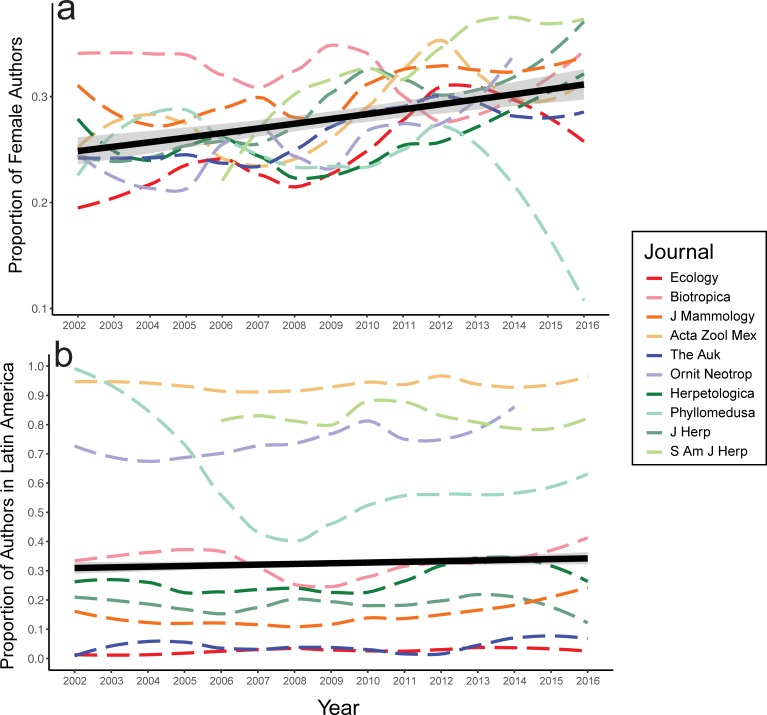

However, whether or not feminine illustration in scientific contributions differs in different areas, equivalent to Latin America, just isn’t properly understood. In this research, in order to find out whether or not feminine authorship is influenced by gender or institutional location of the final (senior) writer or by subfield inside ecology, we gathered writer info from 6849 articles in ten ecological and zoological journals that publish analysis articles both in or out of Latin America.

We discovered that feminine authorship has risen marginally since 2002 (27 to 31%), and varies amongst Latin American nations, however not between Latin America and different areas. Last writer gender predicted feminine co-authorship throughout all journals and areas, as analysis teams led by women printed with over 60% feminine co-authors whereas these led by males printed with lower than 20% feminine co-authors.

Our findings counsel that implicit biases and stereotype threats that women face in male-led laboratories might be sources of feminine withdrawal and leaky pipelines in ecology and zoology. Accordingly, we encourage each PI to self-evaluate their lifetime share of feminine co-authors. Female position fashions and cultural shifts-especially by male senior authors-are essential for feminine retention and unbiased participation in science.

Domesticated Animals on Exhibit on the Museum of Comparative Zoology, 1900-1928.

In 1905 the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard University started planning for a brand new domesticated animals exhibition in honor of the 100th anniversary of the delivery of its founder Louis Agassiz.

The ensuing shows of variation and heredity in poultry, pigeons, rabbits, mice, and guinea pigs proved surprisingly widespread to museumgoers. Some of those specimens nonetheless exist in the museum’s storage amenities, specifically a sequence of poultry donated by the biologist Charles B. Davenport and an elaborate set of guinea pigs from the experimental evolutionist William E. Castle.

Situating these domesticated animal shows inside educational and widespread cultures of poultry fancying, animal breeding, and evolutionary science reveals how a nineteenth-century museum recognized for its ties to anti-evolutionary ideas tried to modernize its public reveals.